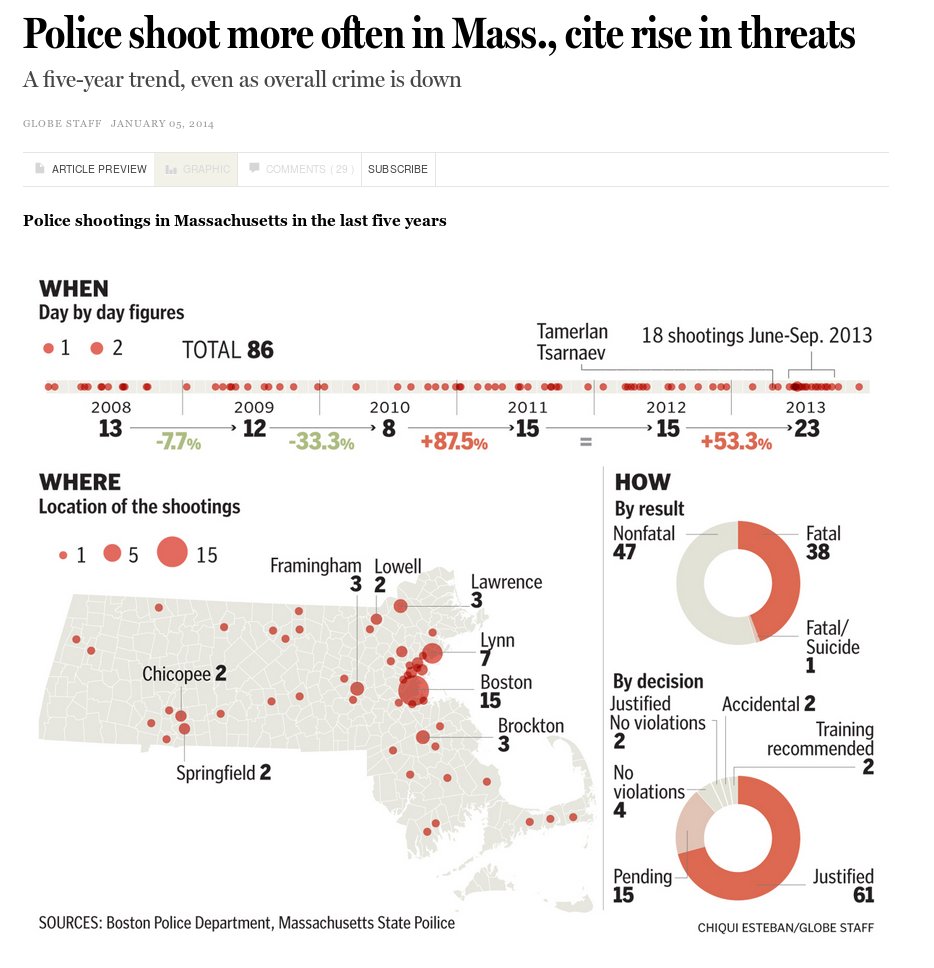

| Police shoot more often in Mass., cite rise in threats | January 5, 2014 |

| Maria Cramer | The Boston Globe |

|

At least 23 people were shot by police in Massachusetts in 2013 - 11 of them fatally, according to figures provided by Boston and State Police, troubling authorities who say the numbers reflect the growing threats police face, and startling civil libertarians who worry about the prevalence of deadly force.

From 2008 through 2013, the number of people shot by officers and state troopers has grown every year. Over that time period, there have been 86 shootings, 67 of which were determined to be justified. Two were classified as accidental, and two led to recommendations that the officers be retrained. The rest remain under investigation. Last year, Boston officials investigated six officer-involved shootings, compared with 1 in 2012. State Police investigated 17 in 2013 compared with 14 in 2012. Police cite two major causes for the uptick in violent confrontations: perpetrators, often mentally ill, who are quick to attack police, and the growing availability of illegal guns. "Guns are everywhere," said State Police Colonel Timothy Alben. "When I started in this department in 1983, if you stopped a car and you seized a firearm, that was a rare occurrence. Today, this is a routine occurrence." Related Every year, he said, State Police seize hundreds of illegal guns - they confiscated 477 illegal firearms from Jan. 1, 2013, to Oct. 31, 2013, the most recent numbers available. Boston police seized 663 firearms in 2013, 125 more than the year before. "There is nothing worse for an officer than having to hurt someone or kill someone," said William Evans, the acting commissioner of the Boston Police Department. "But when we're threatened, we have no other choice." Still, civil libertarians say an upward trend in shootings by police is alarming at a time when overall crime is down across the state. Wilfredo Justiniano, Between 1987 and 2011, the rate of violent crime in Massachusetts dropped 19 percent, according to the state Executive Office of Public Safety. In Boston, the total number of major crimes - such as homicides, armed robberies, and assaults - were down 6 percent from Jan. 1 to Dec. 22, compared with the same time last year. "It's distressing," said Carlton Williams, racial justice attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union in Massachusetts. "Crime is going down. Violent interactions with police should also be going down." All but one of the shootings in 2013 in the state occurred after the Boston Marathon bombings in April, which was followed by a tense five-day manhunt for the two suspects. The manhunt ended in a firefight in Watertown, where one suspect, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, was killed and the other, his brother, Dzhokhar, injured. Transit Police officer Richard Donahue was shot and injured during the chaotic exchange, a shooting believed to be caused by friendly fire. The Middlesex District Attorney's office, which is investigating the Watertown shoot-out, said it is still waiting for reports from the myriad police agencies that responded to complete their investigation. Tamerlan Tsarnaev's shooting was the only one of the Watertown shootings included in the State Police tally. Eugene O'Donnell, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a former New York City police officer, said that in Boston during the bombings and later in Watertown, officers and troopers were essentially in a "war zone." "In Boston you had scenes of war, and the people on the front line of that war were the cops," O'Donnell said. "How much that affects their behavior is an open question." Alben said he does not believe the increase in police shootings since the bombings reflects a police force on edge. "How many interactions do we have with the public over the course of [one] year" Alben said. "There are literally hundreds of thousands . . . on an annual basis and hundreds of them that are done every day. How many of those end up being deadly force situations, I would suggest to you that the percentage is minuscule." It is unclear from the information provided by police exactly how many of the people shot were wielding weapons. Despite a request made in May for police reports detailing the circumstances of each shooting, State Police did not provide the information for this story. State Police investigate shootings in every community except Boston, Springfield, and Worcester. Of of the 73 shootings investigated by State Police between 2008 and 2013, 33 involved troopers and the other 40 involved officers in other departments. Boston Police also did not provide such reports, and Springfield and Worcester did not respond to requests for information. But some of the departments whose incidents were investigated by the State Police gave more details. The Cambridge and Lowell police departments, for example, provided copies of incident reports detailing each time an officer fired a weapon. The cases ranged from shooting a rabid opossum to life-or-death incidents. In April 2008, two Lowell police officers were dispatched to a home where they found a man holding a meat cleaver over his mother's head. When the man refused to put down the weapon and started moving toward the terrified woman, one of the officers shot him in the back. The man survived.

In Boston, where officers killed three of the six people they shot at in 2013, nearly all of the suspects were armed. In June, a private security officer at a Dorchester housing complex shot at an unarmed suspect, grazing him, after police said the man tried to use his car as a weapon. Boston police investigated that case and included it in their total because it occurred in their jurisdiction. Another case investigated by Boston police occurred in July, when a Middlesex deputy sheriff fired at a prisoner after he lunged for another sheriff's gun during a medical visit at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Hospital. The other sheriff was wounded in the struggle when his gun went off. In addition, three Boston police officers were shot during some of the encounters. They all survived. But in some fatal police shootings - those in which the person killed was not wielding a firearm or knife - the circumstances were murkier. In June, Wilfredo Justiniano, a 41-year-old New Bedford man who lived with his mother, was driving through Quincy to visit his father in Boston. For years, Justiniano had struggled with schizophrenia, but, according to his family, he had never been violent. That morning, a driver saw him weaving, clutching his chest, and looking panicked. Worried he might be having a heart attack, she called 911. Trooper Stephen Walker, a 25-year veteran, responded and approached Justiniano, who immediately charged him, according to Norfolk District Attorney Michael Morrissey's final report on the encounter. Walker said he saw Justiniano wielding a pen and ordered him to put it down. "You want it, you're going to have to kill me," Justiniano replied, according to Walker. He lunged at the officer repeatedly, forcing Walker to use chemical spray. Walker said Justiniano kept charging, yelling he would kill him. Walker said he had no choice - he fired two rounds. Justiniano, who was still struggling with police as they tried to handcuff him, was pronounced dead later that morning. A detective showed up at his home in New Bedford. "‘Wilfredo passed away,'" the detective said, as Justiniano's 61-year-old mother, Nora Justiniano, recalled it. The family hired a lawyer, Ilyas J. Rona, who said he has found inconsistencies in witness statements. He declined to be specific. The family is also raising questions about the State Police's policy for dealing with mentally ill people . "There could have been an alternative way, a better way to resolve it," said Justiniano's younger sister, Damaris Justiniano. Alben said eyewitnesses said Walker, who is back on duty, had no other choice but to fire. "We have to put ourselves in the boots of the trooper who responded that day," Alben said. Damaris Justiniano said she wants an outside analysis of the case by her lawyers, who have requested all the documents associated with the investigation. "I don't want another family to go through what we're going through," she said. Justiniano said she hopes such an analysis will force State Police to adopt the use of less lethal weapons, like Tasers, and provide training for dealing with mentally ill people. Alben said that, in general, he dislikes Tasers because he worries officers are too quick to use them. But he said he would like the private sector to develop technology that could disarm a suspect more safely. "In terms of negotiating with someone with mental health [issues], there is not a great deal of training in law enforcement," Alben said. "If there is a shortcoming in any system it's the fact that there aren't those kinds of resources devoted to training." Since 2008, none of the cases cited by state and Boston police resulted in charges of criminal wrongdoing. Alben said he does not believe that any of the shootings by troopers violated the department's policies on excessive force. In Boston, only two of the 13 cases in which a person was shot between 2008 and 2013 resulted in a recommendation of more training for the officer. Details of those cases were not provided. Five of the six shootings that occurred in 2013 remain under investigation, but Evans said he is confident officers responded appropriately. "We're not a department that's trigger-happy," he said. Williams, the ACLU attorney, said that deeming virtually all the shootings justified creates the perception that prosecutors and police resist scrutinizing their partners in law enforcement. "There are ways that police could go about building trust. One of those would be the very strong appearance of responsible, transparent investigations into the shootings and killings by police," he said. "I definitely don't think that appearance is there." Police say they have specially trained investigators, crime scene specialists, ballisticians, and forensic experts who carefully examine every police-involved shooting. "Part of the social compact under which police are given power is a faith that we will properly police ourselves when necessary," State Police spokesman David Procopio said. "State Police stand behind our record of doing that fairly and openly." Morrissey, who investigated the Justiniano case, said the question prosecutors must answer is if a crime has been committed. "There is no easy determination, especially when you're talking about someone losing their life," he said. "This is painful for everyone involved." Todd Wallack of the Globe Staff contributed to this report. Maria Cramer can be reached at mcramer@globe.com and on Twitter @GlobeMCramer.

2013: Fewest Police Deaths (33) by Firearms Since 1887

A job as a police officer attracts psychopaths. A job as a police officer attracts psychopaths (Amazon book). Police, by nature, are criminals. They are individuals who seek a free ticket to rape, pillage and plunder at their own free will. Most have GED's , or at best, with luck, a high school diploma. They do not protect or serve anyone other than themselves in any way, shape, or form. Police commit more crime in one day than any public population in any municipality in the United States. If you are foolish enough to trust a police officer with your life, you commit suicide. They seek a badge to wear to gain immunity from crimes they wish to commit. There has never been nor will there ever be an honest police office. They do not protect us, they harass us. They are misusing their position and authority. Hasn't changed in the last 50 years. Power tripping cops. They aren't even ashamed that they are wasting their time on a useless item instead of earning their money on real crime. Any wonder people disrespect them and they disrespect themselves so much as to have the highest rate of suicide and divorce among workers. Any honest cop knows when to back off. There are too few honest cops.

Law enforcement policy makers base their support of these delayed interrogations on research concluding that the psychological trauma of critical incidents may create perception and memory distortions and, thus, result in statements that could inadvertently contradict other investigatory evidence. These important findings seem consistent with other research indicating that officers experience such effects during events involving the use of force. Drawing from these conclusions, experts have suggested delaying interviews of police personnel for a few hours to several days after a critical incident to enhance investigators' memory and produce more accurate statements. This differs from the practice of immediately questioning civilians. According to conventional wisdom, interviewing or interrogating soon after events produces the most accurate and truthful statements and minimizes the opportunity to fabricate a story. I seriously cannot think of any career with higher incompetence and abuse levels than law enforcement. It just illustrates what happens when you give otherwise nobodies what they perceive as power over others.

|

|

Send comments to:

hjw2001@gmail.com

hjw2001@gmail.com

|